Conservation of the river Nile

Background

The river Nile is an iconic feature of the African landscape and the longest river on Earth. It flows 6700 km from the Great Lakes region of Rwanda and Burundi, through Lake Victoria and northward to Egypt and into the Mediterranean Sea. Its basin covers over a 10th of Africa’s surface area, and its waters support over 300 million people across 11 countries. It is globally important for sustaining freshwater biodiversity and includes multiple areas of outstanding fish richness and endemism.

Innovation

We used cutting edge methods for freshwater planning that incorporate asymmetric connectivity along a river system. However, the most interesting aspect of the analysis is how we developed realistic collaboration scenarios based on the economics and geopolitics of the region. This allowed us to demonstrate that substantial savings can be achieved through collaborative conservation, even when social, economic and political constraining and enabling factors are accounted for.

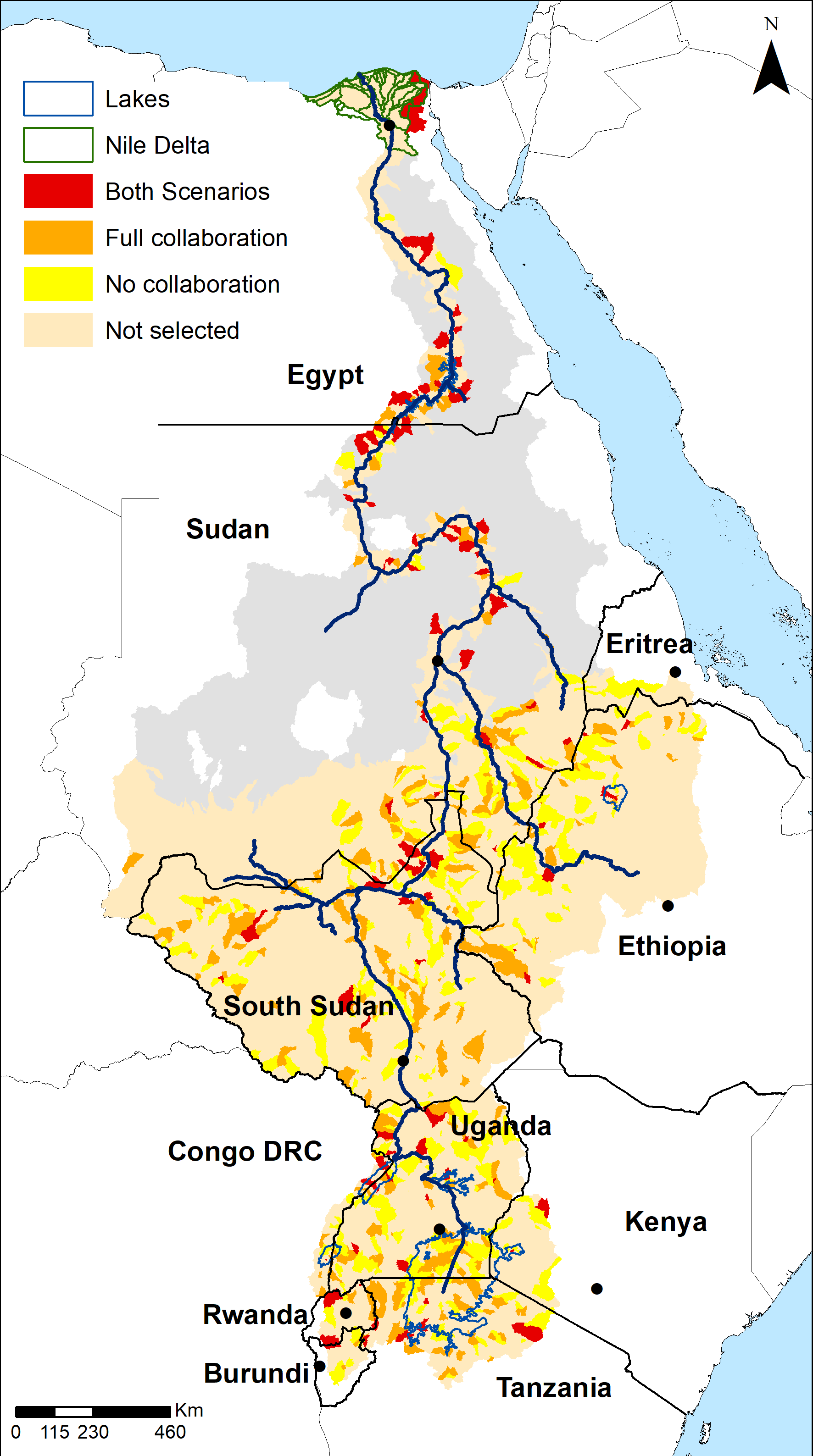

Conservation priorities in the Nile Basin (sub-catchments selected in Marxan’s best solutions) according to the scenario they were selected in, yellow sub-catchments were only selected in the “no-collaboration” scenario, red sub-catchments were selected in the “full collaboration” scenario, and orange sub-catchments were selected in both scenarios.

Conservation priorities in the Nile Basin (sub-catchments selected in Marxan’s best solutions) according to the scenario they were selected in, yellow sub-catchments were only selected in the “no-collaboration” scenario, red sub-catchments were selected in the “full collaboration” scenario, and orange sub-catchments were selected in both scenarios.

We developed the first basin-wide conservation plan for freshwater fish in the river Nile. We identified priority areas for conservation action under different international collaboration scenarios showing how nations can save conservation costs by working together (while still meeting the same conservation targets). Our analyses also accounted for connectivity within the River Nile and the distribution of biodiversity threats.

We compared three collaboration scenarios for the Nile basin. We developed the partial collaboration scenario by quantifying and mapping the strength of potential collaboration among Nile basin countries using a similar framework, in combination with a detailed understanding and discussion of the current politics and historical legacies of the Nile basin.

Many factors affect the likelihood of a country collaborating, including socioeconomic factors such as trade, GDP, and political factors such as governance, corruption, and democracy. We worked off the assumption that, when countries have strong connections in the above categories, they are more likely to collaborate in conservation. We did not account for the geographical distance between countries because we assume that this is also reflected in the other variables (e.g., trade statistics) that we analyzed.

Our international team included political scientists, economists, geographers, ecologists and conservation planners who are either from a Nile Basin nation, or have strong connections with Africa through their work.

Results

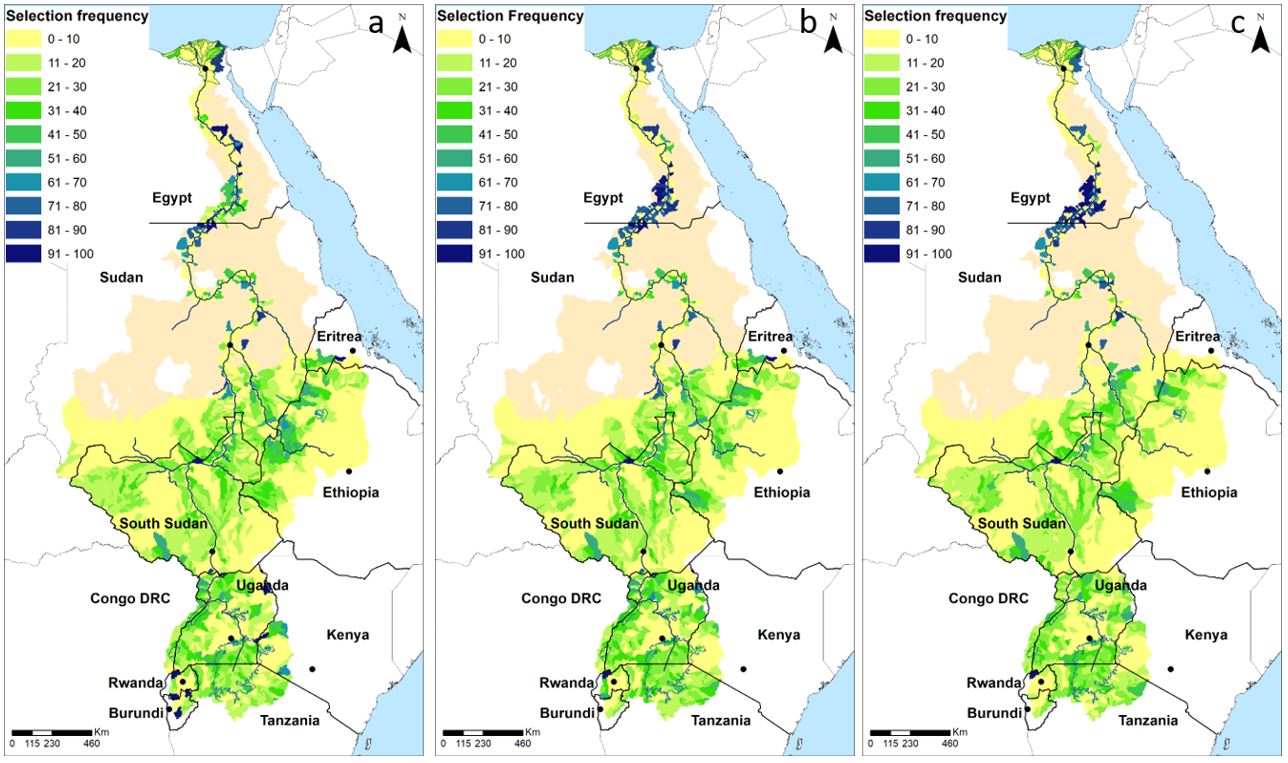

We found that fully coordinated conservation planning is crucial for the Nile basin’s biodiversity as it delivers a substantially less costly conservation outcome than planning for individual African countries without coordination. When each of the Nile basin countries acts independently (no collaboration scenario), the total estimated cost of conservation action in the priority subcatchments is 34% more costly than the fully coordinated basin plan that achieves the same biodiversity targets ($334.4 million and $249.5 million, respectively, as measured by the BHM). The subcatchments identified in the full collaboration scenario are also preferable for conservation investment to those identified in the no collaboration scenario, having lower threat levels (cumulative biodiversity threat scores of 235.5 for the full collaboration and 259.5 for the no collaboration scenario), and support a smaller human population (16 million people for the full collaboration and 25 million people for the no collaboration scenario). We also found that 108 subcatchments were selected as conservation priorities (in the Marxan best solutions) for both the full and no collaboration scenarios, amounting to 26 and 28% of the total selected subcatchments for each of those scenarios, respectively. Conservation priority “hot spots” that were consistently selected across all the collaboration scenarios were evident in several subcatchments, including the Nile delta in Egypt, northern Sudan, and southern Egypt and the East African Great Lakes. Beyond this, there was considerable variation in the spatial location of priority subcatchments across the Nile basin.

Selection frequency of Nile Basin sub-catchments (The number of times each sub-catchment was selected as a priority out of 100 Marxan runs) for a) the “no-collaboration” scenario, b) the “partial collaboration” scenario, and c) the “full collaboration” scenario. Planning units in dark blue were found to be highly irreplaceable for conservation and are therefore conservation priorities, planning units in beige were not included in this analysis.

References:

References

J. R. Allan, N. Levin, K. R. Jones, S. Abdullah, J. Hongoh, V. Hermoso, S. Kark, (2019) Navigating the complexities of coordinated conservation along the river Nile. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau7668

Contact Information:

James Allan

University of Amsterdam

j.r.allan@uva.nl