Transboundary planning in the Pacific

Background

The establishment of eco-regional scale networks of marine protected areas, spanning across national frontiers, is acknowledged as a valid path to safeguard marine ecosystems globally. We planned for regionally feasible networks of marine protected areas, ecologically linked with an existing one. We illustrate our exercise in the Ensenadian eco-region, a highly productive transboundary marine region between the south of California, United States of America (USA), and the north of Baja California, Mexico; where conservation actions differ across the border.

In the USA, California recently established a network of marine protected areas based on scientific design guidelines. Meanwhile, in Mexico: Baja California lacks a system of marine protected areas or a spatial planning effort to establish it. We characterized and collected biophysical and socio-economic information for Baja California and developed novel approaches to quantify and incorporate some of these considerations. This work represented the first effort of an international research group promoting transboundary marine spatial planning in the northwestern Pacific Ocean.

Planning Objectives

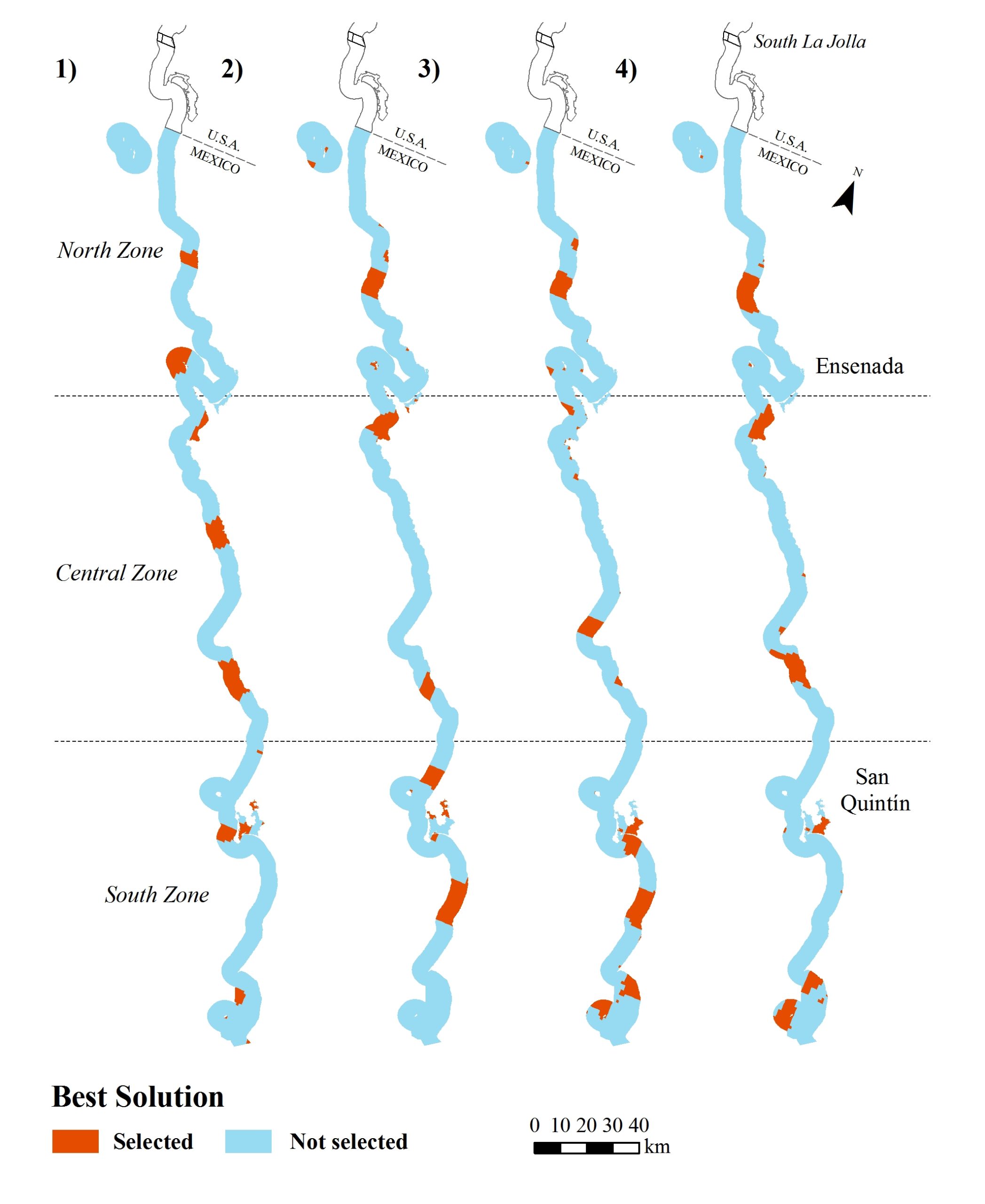

The first objective of our work was to design systems of marine protected areas for Baja California ecologically linked with the existing ones in southern California using the same design criteria. The second objective was to plan for regionally viable networks based on the socio-economic and management context of Baja California.

Planning Objectives

1) Habitat representation

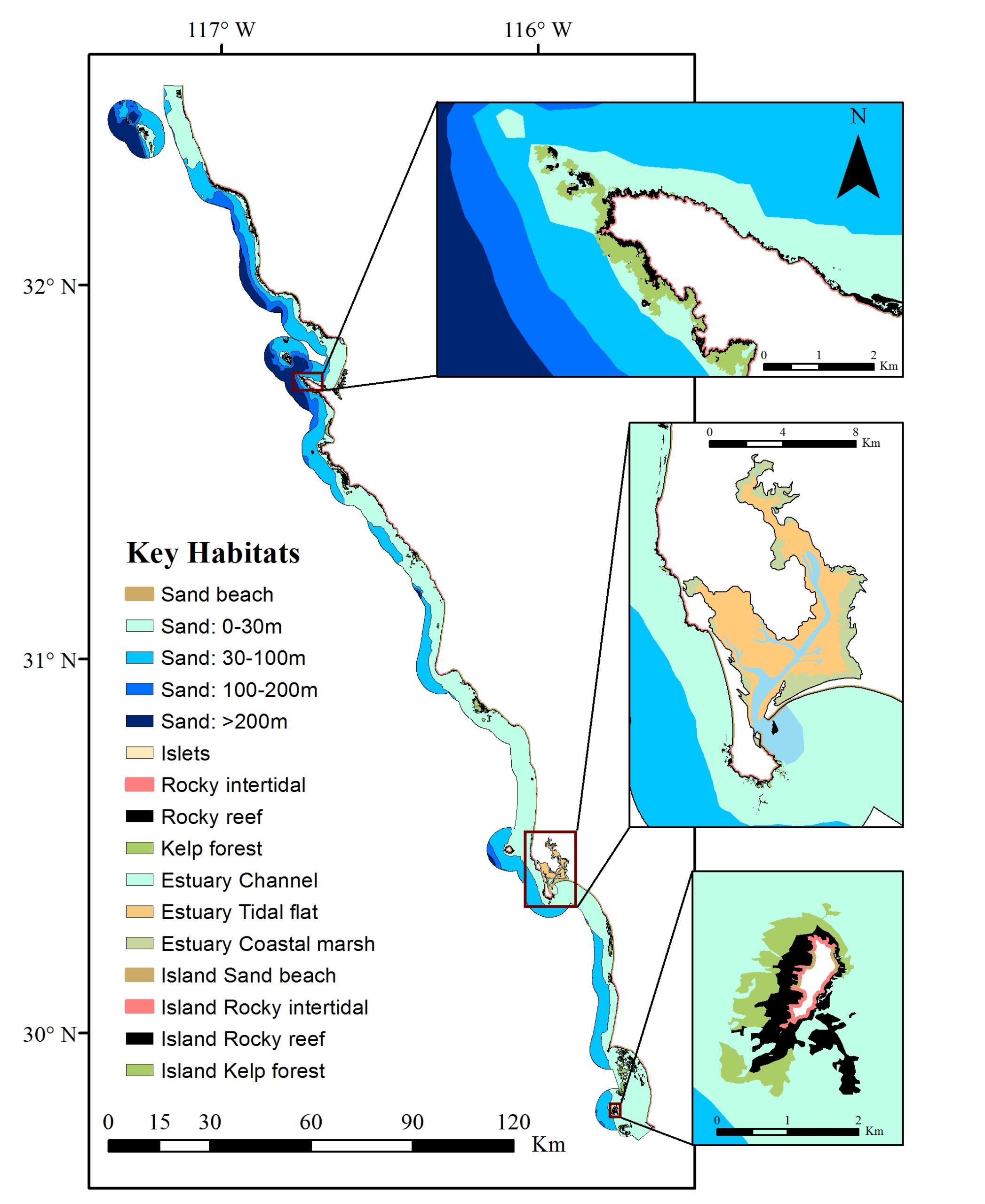

We mapped estuary, intertidal, subtidal, and island habitats. Including the distribution of giant kelp forest in the region, one of the most productive ecosystems in the world.

2) Prioritize habitats in good condition

We used existing cumulative human impact maps to prioritize habitats in better condition.

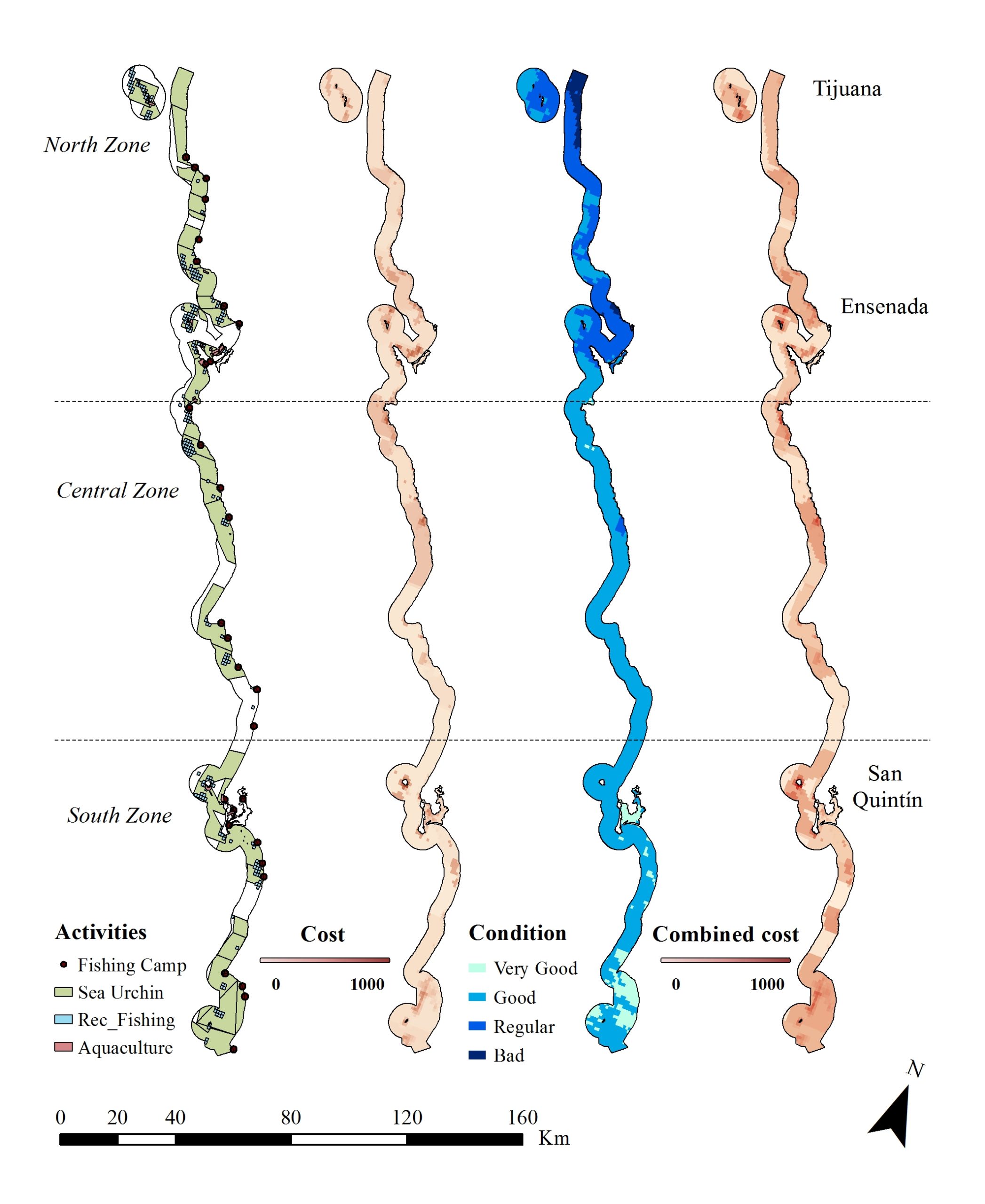

3) Minimize multiple sector opportunity cost

We mapped artisanal fishing activities inside fishing concessions, recreational fishing sites, and aquaculture polygons for Baja California.

4) Prioritize enforcement

We estimated the enforcement capacity inside each fishing concession in Baja California based on their 1) Surveillance capacity, 2) Distance from the fishing camps, and 3) Coast type.

Results

We were able to create baseline spatial products for Baja California to promote future marine spatial planning in the region. We mapped intertidal, subtidal, and estuary habitats (map 1), as well as socio-economic activities for both artisanal and recreational fishing and aquaculture activities (map 2).

In our prioritization approach, all of the marine protected area networks achieved a relatively high percentage of the scientific design guidelines used in California (habitat representation, habitat replication, size of marine protected areas, and distance between marine protected areas). Future networks designed with our approach could protect shared species, populations, communities, and facilitate connectivity between California and Baja California (Map 3).

At a regional level, we were able to design socio-economical viable networks that integrated multiple planning considerations and represented low opportunity costs for fishers and aquaculture investors.

Our work laid the baseline for a marine spatial planning process in Baja California that is being promoted by a large international group of NGOs, researchers, and government agencies.

References:

References

Arafeh-Dalmau et al (2017) Marine spatial planning in a transboundary context: linking Baja, Mexico with California's network of marine protected areas

Contact Information: