Targets and target setting.

In conservation planning targets are the minimum quantity or proportion of the feature (important habitats, species, processes, activities, and discrete areas that you want to consider in your planning process) in the planning region to be included in the solution (e.g. ensure 30% of each habitat type in the conservation system). Targets can also be expressed as an amount (e.g. hectares of a particular habitat) or as the number of occurrences (number of individuals) of every feature that is the focus of the reserve system.

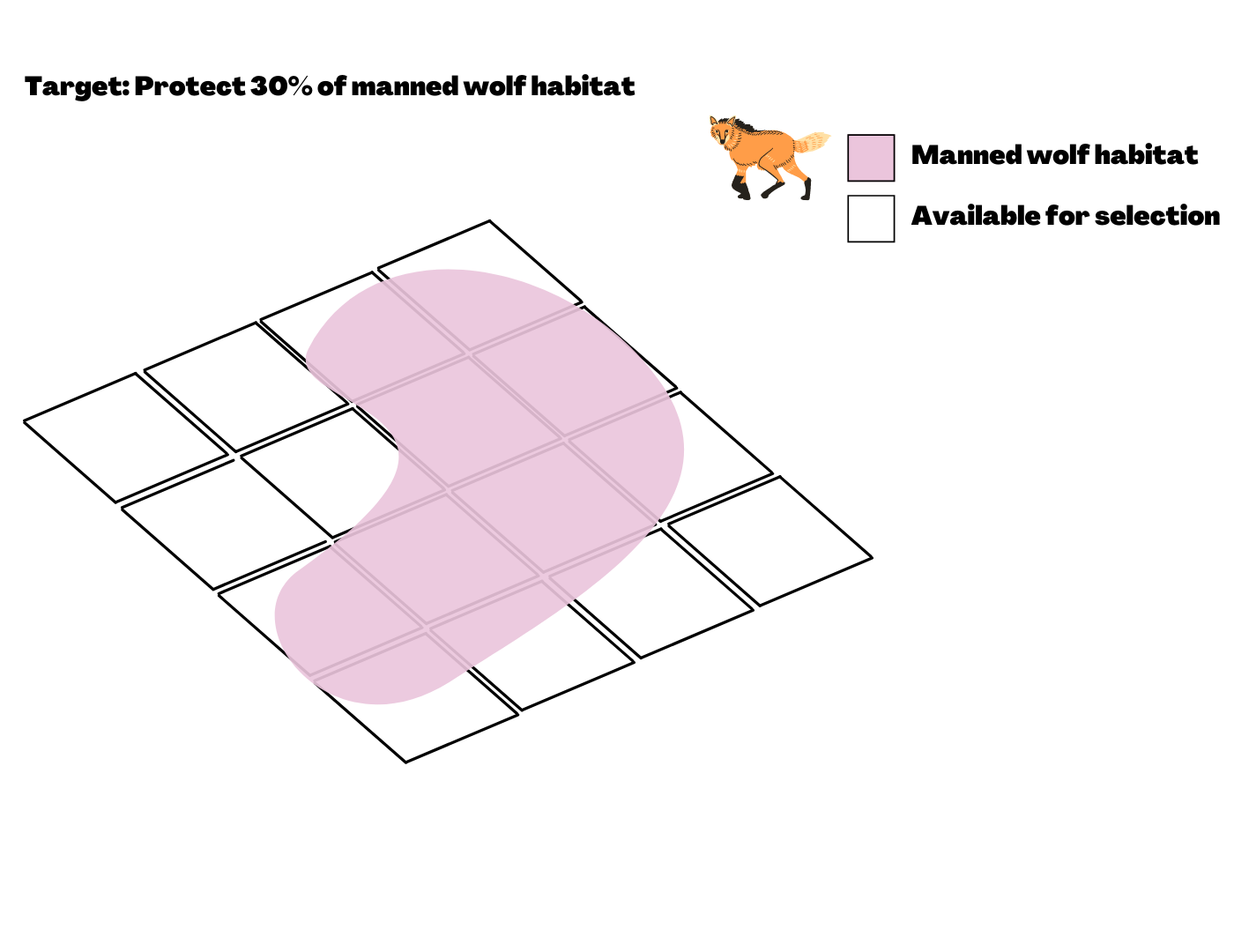

In this example, the Manned Wolf habitat is shown in pink across the planning units that it occurs. Our target is to ensure that 30% of the Manned Wolf habitat is included in our conservation system.

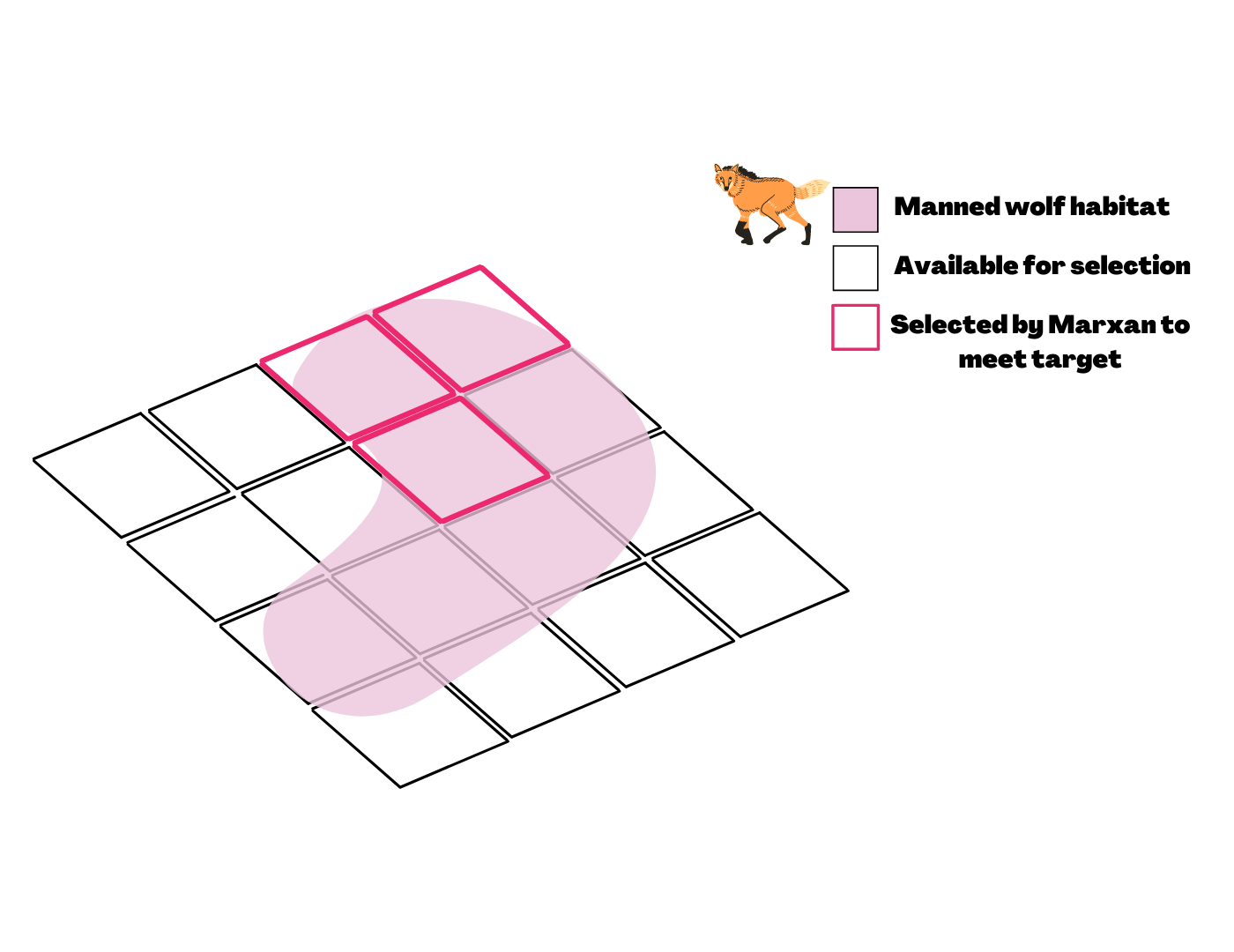

In order to meet the targets, these are the planning units that are selected (in this case by the planning software Marxan) to be included in the conservation network.

THERE ARE MANY DIFFERENT WAYS TO SET TARGETS FOR FEATURES. THESE INCLUDE:

- Expert elicitation

Ideally experts, stakeholders and actors within the region of interest will have an idea about what targets they are trying to achieve based on a good understanding of the local ecology and socio-economic factors at play. However, it is rare that these are readily available. Thankfully there are other ways of setting conservation targets.

- Conservation status as a proxy for target-setting

The conservation status of species and habitats (e.g., IUCN, or national red lists, globally or regionally at risk) can be used to inform priorities and set targets for individual features. Criteria that are commonly used to develop these lists include threat, recent or historical declines, rarity, endemism, or proportional importance, and features that fall into these criteria sometimes receive higher percentage targets. Where species or habitats have declined in extent, data on historic distributions may be available. These can be used to guide setting targets for what remains, as a proportion of its historic abundance. Knowledge on the causes of declines can also help inform target setting. For example, where estuary fish populations are threatened by river obstructions, the ecological objective may be to protect one whole un‐dammed river length from catchment to sea, and the target would be a specified length of unaltered aquatic habitat containing headwater, tributary and mainstream elements.

- Legal frameworks or mandates

Many countries are signatories to conventions or subject to legislation that require a certain proportion of particular species / habitats to be preserved (e.g., the European Community’s Birds and Habitats Directives). This will provide a starting point for setting ecological targets, as well as making them defensible publicly and in a court of law; however, caution is advised, as a legal target may not match what is ecologically required. If there appears to be a discrepancy in this regard, running two sets of scenarios (the “legal” and the “ecological”) can help visually demonstrate the differences in the possible solutions to stakeholders and decision‐makers. Likewise, some organisations have mission statements that commit them to certain targets. Again, these can be run alongside targets based on project‐specific ecological assessments, as well as those created by other stakeholders, government policy, or legal requirements.

- Iterative planning

Achieving broad ecosystem goals, and thus all ecological objectives and Marxan targets that flow from them, should be considered central to any ecosystem‐based analysis. However, pragmatic considerations often require trade‐offs to be made. In exploring trade‐offs, it is a good practice to iteratively explore a range of plausible targets, to document the pros and cons, and the reasoning behind the decisions ultimately made. For example, if experts are unable to agree on a target for a conservation feature, it can be helpful to run different scenarios, exploring these differences. It may be found that they do not make much difference to the reserve design.

- Adjusting targets based on pragmatic considerations

A decision may be taken to lower some targets. For example, if targets are set to represent a percentage of each broad habitat within a study area, even if that percentage is low, it may only be possible for Marxan to meet those targets by selecting very large areas ‐especially if additional constraints are included in the analysis (e.g., locked in areas or fine filter targets for individual species, as discussed above). In such circumstances, the outcome may not be politically or practically achievable, and such targets that drive selection towards large swaths of area may have to be lowered. For the purposes of decision‐making, a final product may include a number of reserve scenarios created based on the same conservation features but a variety of different targets for the features (e.g., 10%, 20%, 30%, etc.), reflecting differing levels of protection, differing conservation costs, and differing risks to species viability and ecological integrity.

FOR MORE INFORMATION.

Ardron, J.A., Possingham, H.P., and Klein, C.J. (eds). 2010. Marxan Good Practices Handbook, Version 2. Pacific Marine Analysis and Research Association, Victoria, BC, Canada. 165 pages. https://pacmara.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/Marxan-Good-Practices-Handbook-v2-2010.pdf

Butchart, S. H. M. et al. (2015) Shortfalls and Solutions for Meeting National and Global Conservation Area Targets. Conservation Letters 8, 329-337, doi:10.1111/conl.12158

Serra, N., Kockel, A., Game, E. T., Grantham H., Possingham H.P., & McGowan, J. (2020). Marxan User Manual: For Marxan version 2.43 and above. The Nature Conservancy (TNC), Arlington, Virginia, United States and Pacific Marine Analysis and Research Association (PacMARA), Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. https://marxansolutions.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Marxan-User-Manual_2021.pdf

Rodrigues, A. S. L. et al. (2004) Effectiveness of the global protected area network in representing species diversity. Nature 428, 640-643, doi: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v428/n6983/suppinfo/nature02422_S1.html

Venter, O. et al. (2014) Targeting Global Protected Area Expansion for Imperiled Biodiversity. PLOS Biology 12, e1001891, doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001891