Scenario Development.

A scenario is an account of a plausible future. Scenario planning consists of using a few contrasting scenarios to explore the uncertainty surrounding the future consequences of a decision. Ideally, scenarios should be constructed by a diverse group of people for a single, stated purpose. Scenario planning can incorporate a variety of quantitative and qualitative information in the decision‐making process. Often, consideration of this diverse information in a systemic way leads to better decisions. Furthermore, the participation of a diverse group of people in a systemic process of collecting, discussing, and analyzing scenarios builds shared understanding. The following section is a summary of Peterson et al. 2003.

Scenario planning begins with identification of a central issue or problem. This problem is then used as a focusing device for assessment of the system; assessment is combined with the key problem to identify key alternatives. Alternatives are then developed into actual scenarios. Scenarios are tested in a variety of ways before they are used to screen policy. Although this overview presents scenario planning as a linear process, it is often more iterative: system assessment leads to redefinition of the central question, and testing can reveal blind spots that require more assessment.

1. IDENTIFICATION OF A FOCAL ISSUE

Because the real world is highly complex and the future contains an infinite number of possibilities, scenario planning must be focused to be effective. Examining the future in light of a specific question (e.g., how ecosystem services could change in Australian rangelands over the next two decades) separates the relevant aspects of the future that are knowable from those that are unknowable.

The focal issue should emerge from negotiation among participants in the planning process. For example, the initial question might be how to maintain a functional longleaf pine forest in a protected area for the next 20 years, or how to make an existing reserve network more robust.

2. ASSESSMENT

The focal issue should be used to organize an assessment of the people, institutions, ecosystems, and linkages among them that define a system. It is also important to identify external changes, either ecological or social, that influence the dynamics of a system. These could include processes as diverse as migration, the spread of invasive species, climate change, or changes in tax laws. A key aspect of assessment is identifying which uncertainties will have a large impact on the focal issue. For example, climatic change may be a key uncertainty in the planning of a protected area system. A subset of these uncertainties will be used to help define scenarios.

One of the most valuable uses of the assessment processes is to confront the initial question or focal issue with the complexity of the world. Does the question address the underlying issue or only its symptoms? For example, managers could decide that determining the optimal configuration of protected areas is too narrow a question and focus instead on how their management could produce a regional landscape that supports biodiversity. An assessment should consider the different world views of the key actors because these views often significantly shape a group’s understanding of a system’s dynamics (Ney & Thompson 2000).

3. IDENTIFICATION OF ALTERNATIVES.

An analysis of the role of uncertainties in the assessment can be used to organize alternatives. Although some uncertainties arise from the unknown future behavior of actors within the system, other uncertainties are based on the unknown dynamics of nature and un-known changes in system drivers. For example, the future of housing development within a watershed may be unknown but can be influenced by local policies. How-ever, the future rainfall of that watershed is uncertain and cannot be influenced by local policies. Scenario planning usually focuses on uncontrollable uncertainties because the attempts of stakeholders to address controllable problems should be included within a scenario’s dynamics.

A set of alternatives can be defined by choosing two or three uncertain or uncontrollable driving forces. For example, if two important uncertainties in a region are population growth and settlement pattern, they could be used to define alternatives such as increased migration to cities, increased migration to rural areas, and general population decline. The uncertainties chosen to de-fine the alternatives should have differences that are directly related to the defining question or issue. They should imaginatively but plausibly push the boundaries of commonplace assumptions about the future. This set of alternatives provides a framework around which scenarios can be constructed.

4. BUILDING SCENARIOS.

Scenarios convert the key alternatives into dynamic stories by adding a credible series of external forces and actors’ responses. Scenarios should become brief narratives that link historical and present events with hypothetical future events. Within these storylines the internal assumptions of the scenario and the differences between stories must be clearly visible. To be plausible, each scenario should be clearly anchored in the past, with the future emerging from the past and present in a seamless way. There are a variety of approaches to assembling scenario stories, including the use of tables or cubes to display critical uncertainties (Schoemaker 1991) and a search for archetypal plots, such as “winners and losers” or “victims become heroes” (Schwartz 1991). Whatever approach is taken, each story should track the key indicator variables that have been selected based on the initial question (e.g., percent of intact old-growth forest, soil erosion). To help communicate and discuss scenarios, it is useful to give each scenario a name that evokes its main features. Successful scenarios are vivid and different, can be told easily, and plausibly capture future transformation.

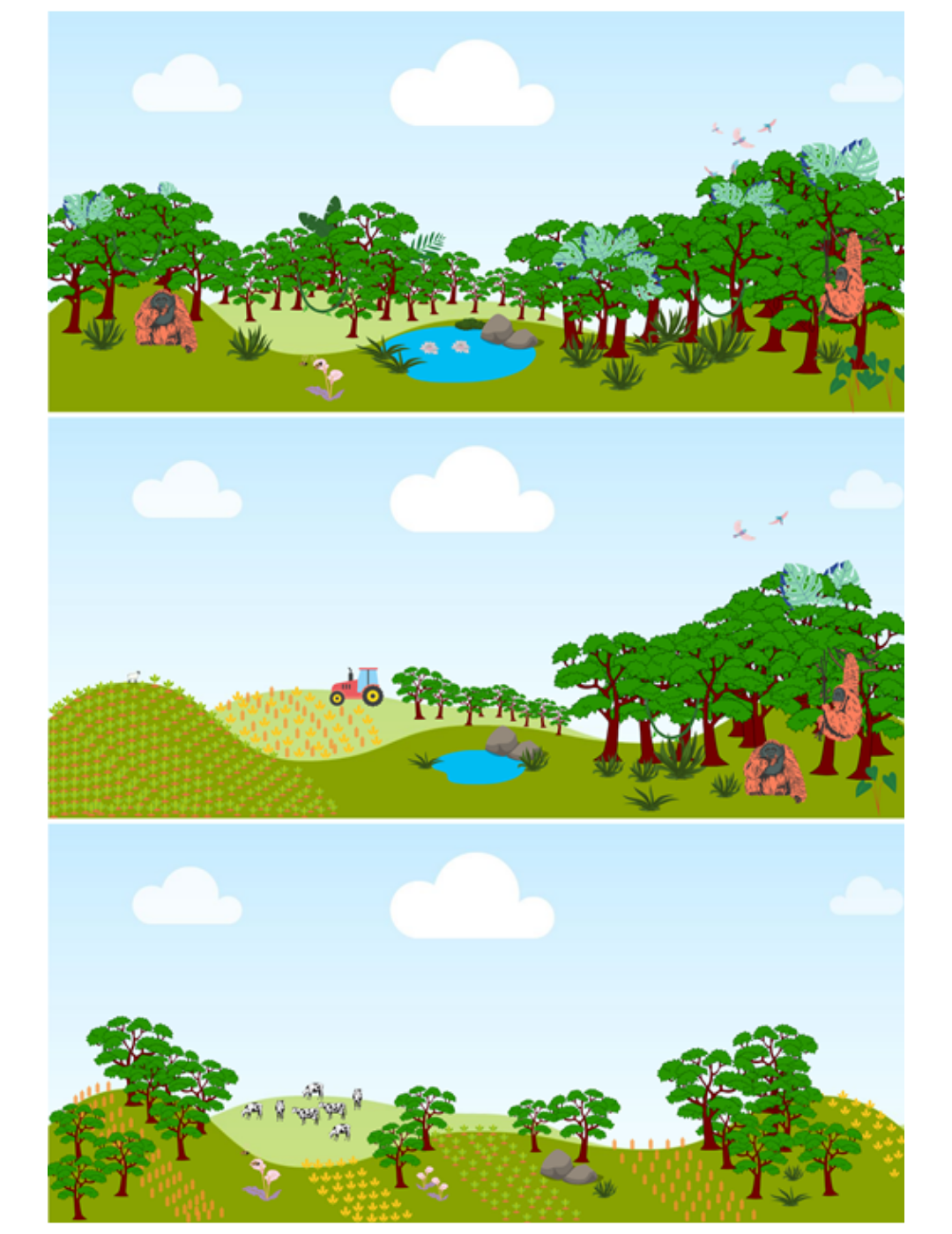

Alternative Futures

5. TESTING SCENARIOS

Once the scenarios have been developed, they should be tested for consistency. The dynamics of scenarios must be plausible; neither nature nor the actors involved in the scenario should behave in implausible ways. In-consistencies will quickly emerge as major obstacles to their usefulness for developing policy. Consistency can be tested by quantification, against stakeholder behavior, through expert opinion, and against other scenarios.

Scenario planning that involves stakeholders can pro-vide a forum for policy creation and evaluation. Stake-holders who become involved in the scenario-planning process are likely to find that some scenarios represent a future that they would like to inhabit, whereas others are highly undesirable. This process of reflection can stimulate people to think more broadly about the future and the forces that are creating it and to realize how their own actions can move the system toward a particular kind of future. In this way, scenario planning allows people to step away from entrenched positions and identify positive futures that they can work at creating. Policy screening often identifies new questions, new variables, and new types of unknowns. These concerns can stimulate either another iteration of the scenario-planning process or another form of action.

A successful scenario-planning effort should enhance the ability of people to cope with and take advantage of future change. Decisions can be made, policies changed, and management plans implemented to steer the system toward a more desirable future. New research or monitoring activities may be initiated to increase understand-ing of key uncertainties, and they may stimulate the formation of new coalitions of stakeholder groups.

REFERENCES.

Peterson, Garry D., Graeme S. Cumming, and Stephen R. Carpenter. "Scenario planning: a tool for conservation in an uncertain world." Conservation biology 17.2 (2003): 358-366. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01491.x

Ney, S., and M. Thompson. 2000. Cultural discourses in the global climate change debate. Pages 65–92 in E. Jochem, J. Sathaye, and D. Bouille, editors. Society, behaviour, and climate change mitigation. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dodrecht, The Netherlands.

Wack, P. 1985 b . Scenarios: shooting the rapids. Harvard Business Review 63: 139–150.

Schwartz, P. 1991. The art of the long view: paths to strategic insight for yourself and your company. Doubleday, New York.

van der Heijden, K. 1996. Scenarios: the art of strategic conversation. Wiley, New York.

Schoemaker, P. J. H. 1991. When and how to use scenario planning: a heuristic approach with illustration. Journal of Forecasting 10: 549–564.